Hag-Seed

Margaret Atwood takes Shakespeare's The Tempest to prison, by way of am-dram revenge.

Margaret Atwood takes Shakespeare's The Tempest to prison, by way of am-dram revenge.If any part of that last sentence sounds remotely appealing, then I think you're going to enjoy this. Hugely entertaining.

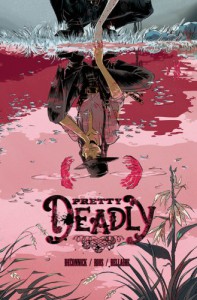

Pretty Deadly, Vol. 1

Attend the song of Deathface Ginny,

Attend the song of Deathface Ginny,And how she came to be

A wrath of rage for men who'd cage

And harm what should be free

Part spaghetti western, part mythical fantasy, Pretty Deadly's first volume flies by in a blur of backstory as it attempts to lay the foundation for the laws that govern the world(s) in which it inhabits. I actually really enjoyed this, but then I'm a proper sucker for alternative takes on the western revenge conventon. I would say, however, that the storytelling is perhaps economical to a fault, and this arc may well have benefitted from being spread over two volumes to give the characters a bit more room to grow.

Still, I'm loving the style and first impressions are good enough to ensure I'll be back for more.

The Road

My initial impressions of The Road were not great. In fact, by page ten or so, I was convinced that I wouldn’t enjoy this book: the prose felt well and truly overcooked and the lack of quotation marks irked me because it added unnecessary confusion to the dialogue. Fortunately, before long, the writing became noticeably less lumpen and I simply stopped caring about the lack of useful punctuation, instead finding myself wholly captivated by the plight of the two nameless principal characters as they struggle to survive in the barren wilderness of a post-apocalyptic American wasteland.

My initial impressions of The Road were not great. In fact, by page ten or so, I was convinced that I wouldn’t enjoy this book: the prose felt well and truly overcooked and the lack of quotation marks irked me because it added unnecessary confusion to the dialogue. Fortunately, before long, the writing became noticeably less lumpen and I simply stopped caring about the lack of useful punctuation, instead finding myself wholly captivated by the plight of the two nameless principal characters as they struggle to survive in the barren wilderness of a post-apocalyptic American wasteland.To describe this book as ‘bleak’ feels like a massive understatement, but - and maybe this is just because I’m a such a morbid weirdo - there’s also something utterly beautiful that permeates through all of the hopelessness and the ever-encroaching finality: yes, the very worst of human nature is well-represented in The Road, but so is the desire to cherish, to protect and to love, and to keep on pushing, keep moving forward, even in the face of an entirely certain outcome; because you have to, because this is what defines us. This is what makes us human.

Radiance

My word, where to begin?

My word, where to begin?I don't think I've ever read anything quite like Radiance before. It doesn't even particularly feel like a Valente novel for the most part. It's complicated, even frustrating at times, but it's also meticulous and beautiful, wistful, brave, melancholy and just downright bizarre. In my feeble capacity to elucidate, here is a list of names and things that may do a better job of capturing some of the essence of this book: Jules Verne, Georges Méliès, Fritz Lang, Roger Zelazny, Ray Bradbury, Forbidden Planet, H.P. Lovecraft, detective noir, murder mystery, Amelia Earhart, William Shakespeare, Greta Garbo, Douglas Fairbanks, Lillian Gish, King of the Rocket Men, Flash Gordon (and just about every other ridiculous Saturday matinee serial you can think of). And I still don't think we’re even getting remotely close. This book ticked so many of my boxes - and quite a few more boxes I didn't even know I had. The blurb describes Radiance as ‘decopunk’, which is both wonderfully accurate and something we need much, much more of.

And yet, beyond all of the retro-futuristic imagery, there lies a story of the difficult relationship between a woman and her movie director father amidst the opulence and decadence of the film industry during its ‘golden age’, her desire to break free of his shadow and become something great in her own right, and the hole that's left in the lives of those closest to her when the unthinkable happens.

This book completely destroyed me in all the best ways.

The Death House

This turned out to be nothing like I expected. In fact, it completely surpassed all of my initial expectations and I just couldn't put it down.

This turned out to be nothing like I expected. In fact, it completely surpassed all of my initial expectations and I just couldn't put it down.Beautifully written and genuinely moving in places.

Hmm... I appear to have something in my eye.

...

...

*sobs violently*

...

Don't look at me! I'm not crying! You're crying!

*flees*

Cages

Proof positive if ever it was required that McKean is not only a phenomenal artist, but also more than capable of holding his own as a story teller.

Proof positive if ever it was required that McKean is not only a phenomenal artist, but also more than capable of holding his own as a story teller.There are some truly wonderful ideas on display here and, though it may all get just a bit too weird at times for some, there's a surprising amount of depth and complexity just beneath the surface, and the dialogue feels particularly natural and convincing (especially for a graphic novel).

My only regret is that I didn't read this sooner.

Speak Easy

This is a retelling of The Twelve Dancing Princesses set during the prohibition era 1920s and focuses on the lives of the residents and staff of the Artemisia, a New York hotel where movie stars rub shoulders with gangsters, artists and politicians; a beacon of hope for the wannabes of the city - the writers, the chorus girls, the 'stars-to-be' - where anybody who wants to be somebody eventually finds themselves; an opulent, hedonistic playground where anything and everything goes.

This is a retelling of The Twelve Dancing Princesses set during the prohibition era 1920s and focuses on the lives of the residents and staff of the Artemisia, a New York hotel where movie stars rub shoulders with gangsters, artists and politicians; a beacon of hope for the wannabes of the city - the writers, the chorus girls, the 'stars-to-be' - where anybody who wants to be somebody eventually finds themselves; an opulent, hedonistic playground where anything and everything goes.Zelda Fair wants to find her calling. Her natural beauty gets her plenty of attention, but she wants more than to be just an object of affection. Frankie the bellboy wants to be a writer, but quite possibly even more than that he just wants Zelda. Al, permanent resident of the hotel's mysterious basement, pulls the strings and arranges the best parties, where, if you play your cards right, you can have everything you ever wanted.

Valente's prose is like a drug. Each meticulously crafted sentence just seems to drip off the page and seep into my brain, releasing a wave of specially manufactured 'magical realism endorphins'. There's a flow, almost a lyrical rhythm to it all, and once I get caught up in that steady stream I literally do not want to be anywhere else. I could probably go on to mention how I didn't think that Speak Easy was particularly perfect, and how the last quarter felt a bit too rushed and uneven compared to the rest of the book, but instead I'll tell you what I did after I finished it.

Ready?

I went and made a cup of tea, then I picked it back up and read it all over again.

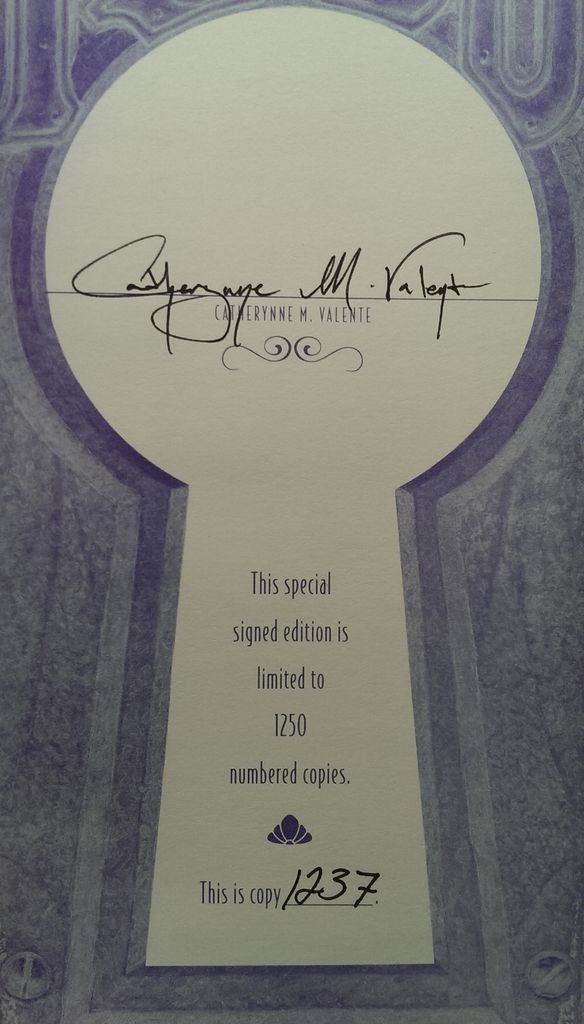

Also: signed copy!

Railsea

Miéville sends up Melville in this rather splendid, brisk and punchy YA fantasy take on Moby Dick, without a single whale anywhere to be found.

Miéville sends up Melville in this rather splendid, brisk and punchy YA fantasy take on Moby Dick, without a single whale anywhere to be found.The world of Railsea is a dry, used up, desiccated and desecrated place; all desert and scrub-land, where humanity is forced to build its settlements on rocky 'islands' above the earth, primarily for survival purposes, and mainly due to the fact that insects and mammals of a huge variety of shapes and sizes can always be found lurking just beneath the surface with only really one thing in common: they would all very much like to eat you. The largest and most terrifying (and most prized) of these creatures is the Moldywarpe, the giant mole.

Across the surface lie thousands, perhaps even millions, of miles of rail tracks, the legacy of a long dead civilization, or perhaps the divine gift of a celestial power, some would say. This is the Railsea, which connects all of the settlements together and allows those of a particularly daring disposition to board trains and venture forth into the wastes to explore, or to scavenge for relics of the past, or to hunt the great beasts of the underneath for glory and profit.

Sham ap Soorap gets a job aboard the moler train Medes as a doctor's assistant. Under Captain Naphi, the Medes is tasked with heading out into the Railsea and hunting for Moldywarpe, but Naphi has a score to settle, and her fixation with the legendary ivory Moldywarpe 'Mocker Jack' puts the crew in a very perilous position. Whilst investigating the ruined shell of a derailed train, Sham finds something that could be a part of something way bigger than mole hunting - a clue leading to potentially discovering where the railsea originated and, more importantly, where the rails actually end - but in order to unravel the mystery he's going to need help. And to somehow get Captain Naphi to change course.

Miéville's real strength is in his ability to create such well-realised, living, breathing worlds, and Railsea is no exception. I'm always particularly fascinated by the sheer depth of imagination he exhibits when creating a sense of place - you can practically taste the air.

All in all, I thoroughly enjoyed Railsea. It's a bit lighter than the usual Miéville fare, but if you're up for a fast-paced dieselpunk/whalepunk (or should that be molepunk?) mash-up adventure, then you could do much worse than picking this up.

The Martian

I was so sure I was going to love this book.

I was so sure I was going to love this book.I mean, I’m really into space science and all of that stuff, and here we have a story about an astronaut stuck on the surface of Mars with limited food and resources and no means of communication with home. I’d also seen numerous snippets of interviews with the author expounding on the lengthy and detailed research he did on near-future space technology to make the story as accurate and plausible as possible. What’s more, every single person I’ve talked to who’d read it thought it was incredible. Oh yes, this was going to be amazing!

So. Three stars, then. Which, roughly translating my own scoring philosophy comes out as something like: Good. Entertaining in its own right, but not particularly life-changing in any way, shape or form. Right now I feel like I’m the only person on Earth who didn’t think this book was completely awesome. Figuratively speaking, I may as well be from another planet. Quite possibly Mars.

A few niggles stopped me from really loving this book, I’m afraid. Let’s start with the ‘technical accuracy’. I have no doubt that Andy Weir went to great lengths in his research to get the technology in The Martian as close to realistic as possible, so why did he choose to almost entirely shun scientific accuracy?

For starters, the atmospheric density of Mars is roughly 1% of that on Earth. So that storm at the start of the book that threatens to blow the module over, causing the crew to evacuate the surface, leaving Watney stranded, injured and alone? Probably wouldn’t have even blown a person over, let alone their MAV. Major plot device fail. Seriously.

Yes, you can burn hydrazine to make water. However, it would have taken much, MUCH longer to produce the amount of water Watney figures out he needs to survive. He’d have probably cooked himself and the hab long before that ever happened. Either way, he’d have been way behind schedule and would almost certainly have starved to death. For what it’s worth, it would have been just as plausible for Watney to simply wave his hands about and cast a level 2 Create Water spell.

There are other problems too that the book conveniently glosses over or just completely ignores for the sake of keeping things simple, such as the potentially disastrous effect that prolonged exposure to the extremely fine dust particles in the Martian atmosphere would have on airtight seals (seriously, Martian dust makes Earth dust look like Mount Rushmore in comparison), or the fact that the hab’s solar cells were simply not efficient enough for the work that they were doing when you consider that the surface of Mars receives (on average) under 600 watts per square metre of energy from the Sun (that’s almost half of what we receive here on the ground on Earth, by the way).

Look, I’m not trying to be a dick about this (though I’m well aware I’m succeeding at it, regardless), and none of the above actually stopped me from enjoying the story, but my eyes did a fair few barrel rolls reading this.

This is what it’s like being me. Pretty terrible, isn’t it?

Okay, so the whole point of making clear how horribly innacurate this made-up science fiction book about something that has never happened and is meant to be purely all a bit of fun is this: over half the book is practically just a list of technical maintenance tasks. Watney goes into an incredible amount of detail as he logs down everything he needs to do in order to stay alive until help can arrive. This is where all of Weir’s research into technical plausibility went, and it shows, but reading chapters and chapters of detailed maintenance schedules with the occasional witticism does not particularly make for compelling reading (especially when the author chooses to just ignore fairly significant facts that would otherwise be inconvenient to the story). The average chapter goes something like this:

1. *Spends the first two pages casually fixing the ‘catastrophic event’ that ended the last chapter on a nail-biting cliffhanger.*

2. Watney needs something. Formulates a plan.

3. Several pages of “I did this. Then fixed this. Attached item X to item Y. If item X fails I’m sooo fucked (hint hint!). Then I did this. Then I say something funny. Now it’s time to test everything works.”

4. “Everything works!”

5. “I miss the crew.”

6. “Fuck disco.”

7. “Oh shit, item X failed. I am sooo fucked.”

Next chapter repeat from point 1.

There’s never any real sense of danger, because each problem is quickly trivialised at the start of the next chapter. Then it’s back to that list of tasks which, let’s face it, is much more interesting!

There’s also almost zero character development. From the little we learn of Watney, he comes across as a two-dimensional sweary class clown with superhuman MacGyver-like engineering skills and a severe dislike of disco. That’s about it. And I can’t even remember what any of the other characters were like, because they all just seemed so similar. The characters based at NASA may as well have all been the same person wearing different name tags.

Shit, this is turning into a rant, which wasn’t my intention. The simple fact of the matter is this: the lack of scientific accuracy utterly negated the effort spent on creating a sense of realism through the means of a meticulous attention to technical detail; I found the characters (aside from Watney) underdeveloped and Watney himself never really makes any particularly poignant observations about his situation other than the occasional joke, which feels like such a missed opportunity; the writing is never really any more than functional, if you don’t count those lists - there's never any real sense of place, and Weir doesn't waste many (if any) words attempting to create a particularly vivid image of the Martian landscape.

Despite this, I enjoyed it for what it was - a fairly straightforward and often very amusing survival story.

I do actually think this will make a better film than it is a book. Mainly because I can’t see Matt Damon spending a good 50 minutes of the running time explaining to the camera exactly what it is he’s doing and why. I’ll still roll my eyes at that fucking storm, though.

Met Office Pocket Cloud Book: How To Understand The Skies

As an amateur astronomer, I spend quite a lot of my free time looking up at the skies. As an amateur astronomer living in the UK, much of that time looking up is actually spent waiting for a gap in the cloud cover. Sometimes this can be a very long wait.

As an amateur astronomer, I spend quite a lot of my free time looking up at the skies. As an amateur astronomer living in the UK, much of that time looking up is actually spent waiting for a gap in the cloud cover. Sometimes this can be a very long wait.I decided, therefore, rather than cursing the hap-hazard weather system of my geographical location, to simply embrace it.

I bought this book some months ago and since then it has become an integral part of my kit. This little book (and it really is little: small enough to fit comfortably into a jacket pocket, if need be) provides enough information about every possible type of cloud formation (including the rarer formations, such as those beautiful, ghostly noctilucent clouds that sometimes appear on calm summer nights), with handy colour photographs for identification, along with the possible weather implications of each type of cloud. There are even pages on 'man-made' clouds and other optical phenomena and atmospheric effects.

This is such a wonderful, informative little book with the power to transform a frustrating astronomy session into something fascinating.

A little knowledge never hurts, and all you have to do is look up! A perfect companion for any lazy day out in the open air.

Embassytown

I had a brief internal debate about whether I enjoyed Embassytown's story enough to warrant the five stars, but whatever; the underlying concept of this novel just completely blew my mind.

I had a brief internal debate about whether I enjoyed Embassytown's story enough to warrant the five stars, but whatever; the underlying concept of this novel just completely blew my mind.You win this round, Miéville. Five stars all the way.

Hyperbole and a Half

I found myself able to relate pretty closely to quite a few of the stories and situations in this book. Should I be at all worried...?

I found myself able to relate pretty closely to quite a few of the stories and situations in this book. Should I be at all worried...?Erm, anyway, I was holding it all together pretty well until I got to that story about the goose, and then I literally just completely lost it. I mean totally. I'm talking one of those rolling around, eyes streaming with tears, please let me breath in before my lungs implode kind of moments.

Painfully hilarious.

A Slip of the Keyboard: Collected Non-Fiction

”My name is Terry Pratchett and I am the author of a very large number of inexplicably popular fantasy novels.

”My name is Terry Pratchett and I am the author of a very large number of inexplicably popular fantasy novels.Contrary to popular belief, fantasy is not about making things up. The world is stuffed full of things. It is impossible to invent any more. No, the role of fantasy as defined by G. K. Chesterton is to take what is normal and everyday and usual and unregarded, and turn it around and show it to the audience from a different direction, so that they look at it once again with new eyes.”

Most people know Terry Pratchett as “that bloke with the hat who wrote those comedy fantasy books” and, generally speaking, if they’ve ever read a Discworld book then they’ve most likely picked up one of the early ones, probably thought it was all “a bit of a wheeze” and all, but nothing really life-changing, maybe even a bit too silly and old-fashioned, said to themselves well, I’ve tried Pratchett now, so I can get on with bigger and better things, and promptly did just that. And that’s fair enough.

But, over the years, Pratchett’s writing evolved considerably, and the Discworld expanded into something bigger and so much better. The early novels are all fairly simplistic parodies of various aspects of the fantasy genre with a little bit of real-world satire thrown in for good measure to raise a knowing smile here and there, but as the Discworld grew into it’s own fully-fledged universe with its own well-defined continents, races, cities, heroes and villains and regular, everyday folk alongside all the witches and wizards, assassins, ponginae bibliothecus, aging barbarians, anthropomorphic personifications (oh, and Corporal Nobby Nobbs, who deserves a distinct classification of his own) and Cut-Me-Own-Throat Dibbler’s Sausage inna bun ‘meat’ products, the parody and fantasy-lite aspects gave way almost entirely to the satire, and the Discworld - now with it’s own established history, mythology and philosophy - became a magical, often ridiculous, but pretty much always right on the money, mirrored reflection of ourselves.

And this is the reason why I love, and will always love, Terry Pratchett. Yes; he wrote about trolls and dwarves and zombies and golems amongst a myriad of other fantastical things, but it was all just an elaborate and cunning ruse to write about us - from gender and racial politics, to religion, war, extremism, old age, bureaucracy, vampires*, education, immigration, science, wonder, beauty, death… you get the idea. I think Sir Terry was a true philosopher at heart: he seemed to have it all figured out, seeing the world unfiltered, as it is, and could communicate this not only in a style that was uncomplicated and (at least seemed) so effortless, but with so much humour, style and heart. I miss him terribly already**.

And it is with this thought that I’ll (finally) come to A Slip of the Keyboard.

This was a difficult read for me at times. I think I may have picked it up too soon after Sir Terry’s death, in all honesty.

The first two parts are a collection of musings, essays, newspaper articles, lectures and speeches that Pratchett wrote for various occasions on a wide-ranging number of topics. Most are prefaced with a very brief comment by the author himself explaining the when’s/where’s/why’s of each piece. The vast majority are Classic Pratchett - by which I mean interesting, informative and (usually) rather amusing. Topics include: Sir Terry’s original childhood inspirations for becoming a fantasy writer; a defense of science fiction and fantasy; a diary of a signing tour in Australia; conventions; a piece about Neil Gaiman; hats!; home life; fans; writing; Discworld; several acceptance speeches, plus a great deal more. There are some truly wonderful pieces, and you do get a real sense of the man behind the word processor. My only niggling complaint here is that there is some overlap between the contents of some of the speeches at times, which makes reading too many in one go become a wee bit of a déjà vu-like experience. It’s less a complaint about the contents of the pieces themselves and more of the way in which they’ve been ordered, I suppose.

The final part, entitled Days of Rage, is of an entirely different tone. Here, we see another side to Pratchett - a collection of pieces written on topics that the author feels passionate enough about to give voice to his dissent in public: the state of the education system; the slow, lingering death of the National Health Service; the plight of the Orangutan in the face of the mass-deforestation of Borneo. But by far the hardest hitting pieces here are the ones written after Sir Terry was diagnosed with posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), a rare form of Alzheimer’s disease, in which he describes, often in painful detail, his increasing difficulties with everyday life. One piece moved me so profoundly that, after finishing it, I put the book down and couldn’t bring myself to pick it back up for about a week. Pratchett is very open about his experiences, from the frustration and humiliation of no longer being able to get underpants on the right way round on the first try, to the despair associated with the realisation that his ability to continue writing is severely impacted without external help. There’s no sense of self-pity, though: these pieces are fueled entirely by anger - anger aimed squarely at the disease - the disease which he so famously referred to as “the Embuggerance” on many occasions. Here in Britain, Sir Terry used that anger over the last few years of his life to campaign for increased awareness for sufferers of Alzheimer’s, along with providing his support for the Right to Die campaign for the terminally ill. The last two pieces of the book describe his visit to one of the Dignitas ‘assisted suicide’ facilities in Switzerland whilst making a documentary for the BBC, his experiences there meeting people undergoing the ‘treatment’, and a brief summary of the reactions of the public and press once the documentary aired.

A book of polar opposites, then: both fun and entertaining, yet also serious and deeply moving.

I can’t possibly conceive giving this book any less than five stars. A must-read for Terry Pratchett fans.

* Quite possibly not a real-world issue, but The National Enquirer suggests otherwise.

** There’s one finished book left to come, The Shepherd’s Crown, which is a Tiffany Aching novel (arguably part of the best arc on the Disc), this September. I still don’t know if this news makes me deliriously happy or just really, really sad, knowing that it’s truly the very last one ever. /sadface

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is historical fantasy. It is Jane Austen writes magical realism; it is Harry Potter for the Classic Romance crowd; it is a Regency-era Silmarillion. It is all these things and so much more. It is a novel in the most traditional sense - and it is bloody brilliant.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is historical fantasy. It is Jane Austen writes magical realism; it is Harry Potter for the Classic Romance crowd; it is a Regency-era Silmarillion. It is all these things and so much more. It is a novel in the most traditional sense - and it is bloody brilliant.That isn’t to say everyone will enjoy it; far from it. If the mere mention of 19th century fiction brings you out in a flourish of hives, then I think it’s a very safe bet that you’re going to absolutely hate this book. Clarke manages to emulate the style of Georgian/Regency fiction convincingly and deliberately - Austen in particular, though there’s more than a pinch of Mrs. Radcliffe, and some of the characters are downright Dickensian in their eccentricities - right down to the use of archaic alternative language. It’s all very immaculately constructed and, certainly for the first half of the novel, you may find yourself forgetting that this is the work of a contemporary author. Thankfully, Clarke doesn’t leave her modern sensibilities completely behind, and sticky issues like 19th century gender politics and racial discrimination are treated with tongue firmly in cheek.

The story itself concerns the return of magic to England, via the eponymous Norrell and Strange: the former being rather dour, dry and utilitarian; the latter young, charismatic and eager to impress. Of course, in order for magic to return to England, it must have existed at some point in the first place - so to this end, Clarke constructs an elaborate, extensive mythology to her version of England’s history via footnotes and exposition, weaving together little pieces of faerie folklore to breathe life into the legend of the Raven King - which is actually so well-realised that you’ll want to believe that it’s actual folklore and not just made up for the book (and, yes; I’m well aware folklore isn’t really real, but you know what I meant - it’s still rather fascinating!).

I was particularly impressed by Clarke’s use of the ‘Fae Folk’, actually - these faeries are certainly not the diminutive, butterfly-winged forest spirits romantically popularised by the Victorians and sensationalised later by the Cottingley photographs; nuh-uh. These are traditional faeries. The kind that made fairy-stories the cautionary tales that would strike fear into the hearts of their listeners. The kind that see mortals as mere playthings; that kidnap both children and adults alike; or offer promises of power and wealth to the hapless and unwary, only to deceive and betray them for their own amusement. Beautiful, arrogant and, above all else, dangerous. Proper faeries.

Given that this is a book primarily about magic and faeries, I find it quite astonishing how well all the fantasy weaves seamlessly into the actual history of the period. The growing popularity of our titular magicians gives Clarke reason enough to introduce a number of famous names and events into the story, from the Duke of Wellington to Lord Byron, with some suitably wonderful encounters. Clarke even rewrites the events leading up to the end of the Napoleonic war to include England’s newly rediscovered ‘secret weapon’!

A thoroughly enchanting novel, in every sense of the word.

If this sounds even moderately interesting to you, then I’d advise that you remove yourself from the drawing room post-haste (the servants can show the guests out), and retire to your favourite fireside chair in the library with a pot of tea and a small tray of cakes and other delicate fancies. Oh, and don’t forget the book. You can thank me the next time we cross paths at one of the more fashionable balls in Bath.

1

1

U.S. Secret Service agent Ethan Burke wakes up on the outskirts of Wayward Pines - a sleepy, idyllic little town in rural Idaho - with almost no recollection of how he got there, except for the lingering memory that he’s been sent to investigate the disappearance of two federal agents. Battered, bruised and suffering from concussion (as well as missing both his wallet and any official proof of his credentials), Burke heads out determined to complete his mission, but quickly begins to suspect that Wayward Pines isn’t the tranquil mountain burg that it appears to be. Before long, both his sanity and his life are in grave danger.

To give any more plot details away would ruin the mystery, which is pretty much the whole point of the book - therefore, I’ll try exceptionally hard to be as vague and spoiler-free as I can be for the rest of... whatever this thing is I’m typing right now. (I can never keep a straight face when I refer to any of my incoherent ramblings as “reviews” *cough*)

Pines is, by the author’s own admission, heavily inspired by Twin Peaks and on the surface they do appear rather similar (at least initially), but Crouch draws pretty deeply from the Well of Outlandish Conspiracy Stories, so you’ll find plenty of other recognisable elements here: Wayward Pines itself owes more than a passing resemblance to (that bastion of chauvinistic reverie) Stepford, with its rows of gaily painted houses and cheery welcoming faces, along with various other bits and pieces you’ll swear you’ve seen before from the likes of Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, They Live!, The X Files, The Twilight Zone… Well, you get the idea. I’m not trying to diminish Crouch’s efforts though, because he manages to pull off the heightened levels of sinister tension, suspense and growing horror that you expect from such stories with plenty of flair, effectively managing to give Pines enough of an identity to be appreciated on its own merits. That’s not to say I didn’t have my share of problems with it, though.

Problem 1. Have you ever had the feeling that a book is actively trolling you? No? Well, you may feel differently once you've read this novel.

By its very nature, Pines is a multi-layered mystery novel. Like Burke, we’re not meant to know what’s really going on in Wayward Pines until the final “Big Reveal” but, as those layers are gradually stripped away and the truth is uncovered, you’d at least hope that the pieces would start to coherently fit together and things would make some kind of sense, maybe? Nuh-uh. Crouch throws in so much misdirection and so many twists in the narrative that it’s almost impossible to get a proper handle on what’s actually supposed to be going on. Whenever you start to think “riiight, I see where this is going” then *BAM*: U-turn. Plot threads that lead to nowhere; characters that do weird things for no real reason; and a much-hyped love triangle situation that is seemingly only present to serve as an eyebrow raising plot-device in one single scene.

I wouldn’t mind, honestly - I like surprises! And weirdness! And I acknowledge that not all things need to make sense! - but it all feels just a bit too contrived. Deliberately random. After certain chapters I couldn’t help but picture an image of Blake Crouch in my mind, sitting at his keyboard sporting a trollface meme expression, chuckling away to himself at how deviously he was manipulating the story. Sigh.

Problem 2. The “Big Reveal”. Not particularly terrible, but completely changed the tone of the novel (and presumably the next books in the series) into something else entirely, instantly transforming it into just another title amongst a burgeoning list of novels in a certain overplayed genre that I can’t talk about lest I spoil everything for everyone. Meh.

Problem 3. Ethan Burke is an utter jerk. Seriously. Crouch basically paints our hero as a selfish, arrogant A-hole almost from the beginning, then expects us to root for him as he runs rampant through Wayward Pines attempting to dictate his super-special Secret Service authority over everybody despite not actually having any identification to back up his claims. Yes, I realise this is a man under a lot of pressure. He’s also a military veteran with a past that has left him both physically and psychologically scarred - and maybe I’d feel differently and more sympathetic if the most hazardous thing in my life wasn’t just occasionally reading YouTube comments - but, if it acts like an entitled dick, and talks like an entitled dick, then chances are... Yeah.

These problems aside, I still enjoyed Pines. Crouch, despite that damned trollface, writes really well and the pages just flew by. Indeed, even amidst all the confusion and the highly improbable grimace-inducing moments, I found it hard to put the book down. I do love a good crazy conspiracy theory story *adjusts tinfoil hat* and Pines satisfies that itch for the majority of its length. I’m certainly going to check out book two in the series in the (slim) hope that it doesn’t devolve into a by-the-numbers generic entry in a certain other genre - but then, I’m also not holding my breath.

To give any more plot details away would ruin the mystery, which is pretty much the whole point of the book - therefore, I’ll try exceptionally hard to be as vague and spoiler-free as I can be for the rest of... whatever this thing is I’m typing right now. (I can never keep a straight face when I refer to any of my incoherent ramblings as “reviews” *cough*)

Pines is, by the author’s own admission, heavily inspired by Twin Peaks and on the surface they do appear rather similar (at least initially), but Crouch draws pretty deeply from the Well of Outlandish Conspiracy Stories, so you’ll find plenty of other recognisable elements here: Wayward Pines itself owes more than a passing resemblance to (that bastion of chauvinistic reverie) Stepford, with its rows of gaily painted houses and cheery welcoming faces, along with various other bits and pieces you’ll swear you’ve seen before from the likes of Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, They Live!, The X Files, The Twilight Zone… Well, you get the idea. I’m not trying to diminish Crouch’s efforts though, because he manages to pull off the heightened levels of sinister tension, suspense and growing horror that you expect from such stories with plenty of flair, effectively managing to give Pines enough of an identity to be appreciated on its own merits. That’s not to say I didn’t have my share of problems with it, though.

Problem 1. Have you ever had the feeling that a book is actively trolling you? No? Well, you may feel differently once you've read this novel.

By its very nature, Pines is a multi-layered mystery novel. Like Burke, we’re not meant to know what’s really going on in Wayward Pines until the final “Big Reveal” but, as those layers are gradually stripped away and the truth is uncovered, you’d at least hope that the pieces would start to coherently fit together and things would make some kind of sense, maybe? Nuh-uh. Crouch throws in so much misdirection and so many twists in the narrative that it’s almost impossible to get a proper handle on what’s actually supposed to be going on. Whenever you start to think “riiight, I see where this is going” then *BAM*: U-turn. Plot threads that lead to nowhere; characters that do weird things for no real reason; and a much-hyped love triangle situation that is seemingly only present to serve as an eyebrow raising plot-device in one single scene.

I wouldn’t mind, honestly - I like surprises! And weirdness! And I acknowledge that not all things need to make sense! - but it all feels just a bit too contrived. Deliberately random. After certain chapters I couldn’t help but picture an image of Blake Crouch in my mind, sitting at his keyboard sporting a trollface meme expression, chuckling away to himself at how deviously he was manipulating the story. Sigh.

Problem 2. The “Big Reveal”. Not particularly terrible, but completely changed the tone of the novel (and presumably the next books in the series) into something else entirely, instantly transforming it into just another title amongst a burgeoning list of novels in a certain overplayed genre that I can’t talk about lest I spoil everything for everyone. Meh.

Problem 3. Ethan Burke is an utter jerk. Seriously. Crouch basically paints our hero as a selfish, arrogant A-hole almost from the beginning, then expects us to root for him as he runs rampant through Wayward Pines attempting to dictate his super-special Secret Service authority over everybody despite not actually having any identification to back up his claims. Yes, I realise this is a man under a lot of pressure. He’s also a military veteran with a past that has left him both physically and psychologically scarred - and maybe I’d feel differently and more sympathetic if the most hazardous thing in my life wasn’t just occasionally reading YouTube comments - but, if it acts like an entitled dick, and talks like an entitled dick, then chances are... Yeah.

These problems aside, I still enjoyed Pines. Crouch, despite that damned trollface, writes really well and the pages just flew by. Indeed, even amidst all the confusion and the highly improbable grimace-inducing moments, I found it hard to put the book down. I do love a good crazy conspiracy theory story *adjusts tinfoil hat* and Pines satisfies that itch for the majority of its length. I’m certainly going to check out book two in the series in the (slim) hope that it doesn’t devolve into a by-the-numbers generic entry in a certain other genre - but then, I’m also not holding my breath.